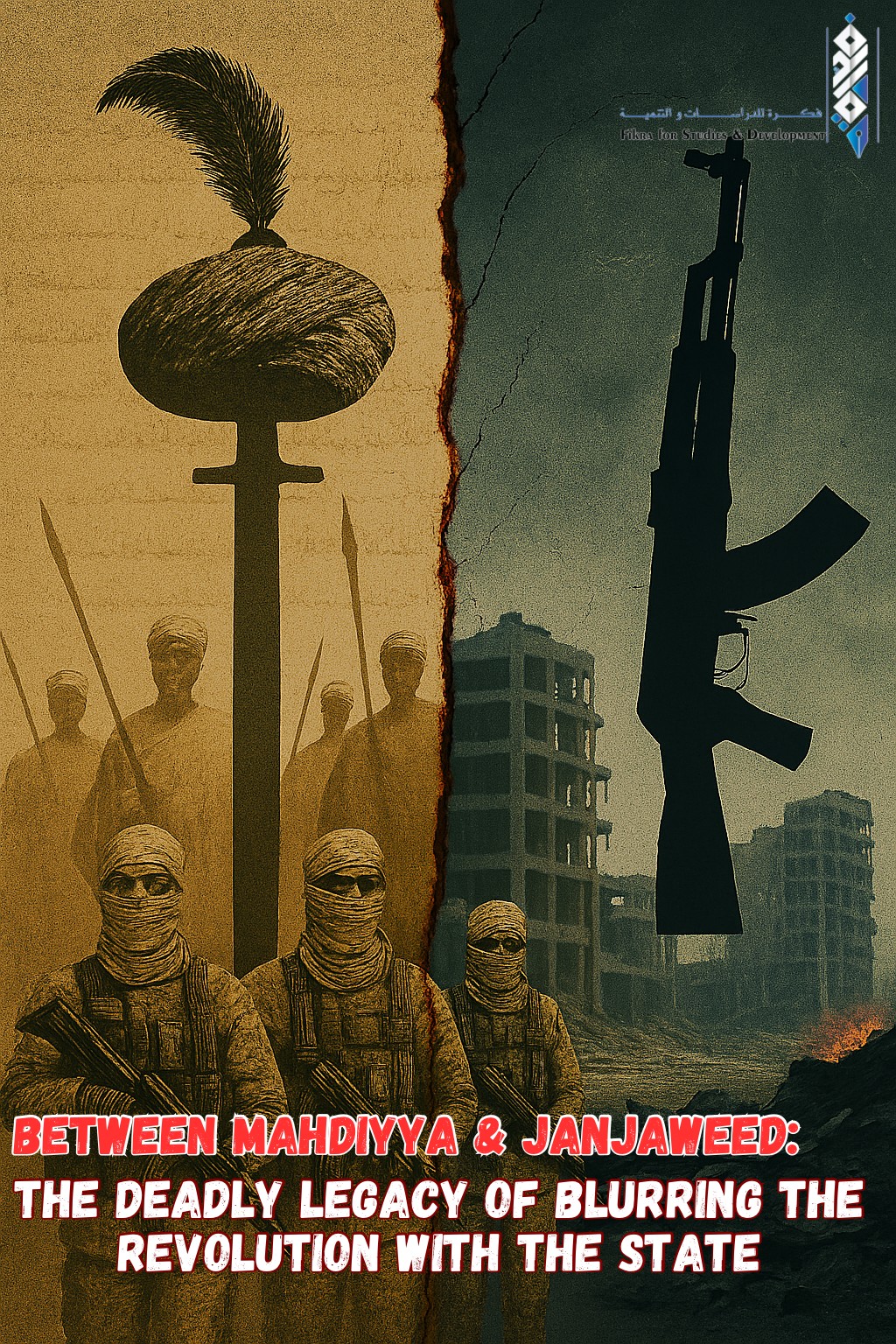

Between Mahdiyya & Janjaweed: The Deadly Legacy of Blurring the Revolution with the State

Between Mahdiyya & Janjaweed: The Deadly Legacy of Blurring the Revolution with the State

Amgad Fareid Eltayeb

September 6, 2025

The Sudanese nation is enduring the most violent ordeal in its modern history, amid a grinding war that has threatened the state’s existence, displaced its people, inflicted unimaginable suffering, and reduced its fertile land to rubble and ashes. Since the outbreak of war in April 2023 between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the Rapid Support Forces militia, hundreds of thousands have lost their lives as a result of fighting, hunger, and disease. Over 12 million people have been displaced internally, and more than 4 million have sought refuge abroad, making it the world’s largest displacement crisis. Meanwhile, the deliberate use of starvation sieges as a weapon of war has triggered a catastrophic famine in various regions of the country. The chapters of this tragedy continue to unfold as fighting persists across the nation.

This war is not merely a military clash between Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (Hemedti). Rather, it stems from a failed coup that ignited a conflagration, shaking state’s foundations, destroying its already crumbling infrastructure, and exploiting the disintegration of its social fabric. The cycle of violence has expanded by—among other factors—an epistemological trap that prevents learning from history, instead using it as fuel for further flames of war.

Recently, political commentary on social media platforms and in public discussions has sparked debate about the nature of the current war. Some have drawn comparisons between the crimes and violations of the Rapid Support Forces militia and the violence witnessed during the era of the Mahdist state, particularly under the rule of Khalifa Abdallahi al-Ta’ayshi after the death of the Mahdi, which occurred mere months after the liberation of Khartoum from Turkish colonial rule on January 26, 1885.

The Mahdist Revolution: Tales of Revolutionaries and Politicians

Muhammad Ahmad al-Mahdi (August 1844–June 1885) began early to express his discontent with Sudan’s deteriorating conditions—a result of Turkish colonial rule and the exorbitant, burdensome taxes imposed by its authorities. In late 1880, al-Mahdi met Abdallah Wad Torshin (al-Ta’ayshi) in the village of Tayba in central Sudan. Historians widely recount that al-Ta’ayshi played a pivotal role in convincing al-Mahdi to proclaim his Mahdism and was the first to pledge allegiance to him. In return, al-Mahdi declared him as his successor based on a revelation he claimed to have received in a prophetic vision.

Abdallah al-Ta’ayshi (1846–1899) was born in the village of Um Dafuq in Dar al-Ta’aysha in southern Darfur. He received his religious education in the Sudi order of Sheikh Muhammad Sharif Nur al-Da’im. Al-Ta’ayshi was known for propagating the idea that the awaited Mahdi had appeared, and that denying him constituted blasphemy. However, his sheikh Muhammad Sharif forbade him from this, and he desisted. During the war of al-Zubayr Pasha in Darfur, Abdallah was captured in some battles in the Shakka region. Al-Zubayr intended to kill him, but some scholars interceded, and he pardoned him. Al-Ta’ayshi then sought to reward al-Zubayr for his mercy by trying to convince him that he was the awaited Mahdi, confiding to him: “I saw in a dream that you are the awaited Mahdi, and that I am one of your followers.” Al-Zubayr replied: “I am not the Mahdi; rather, I saw these Arabs blocking trade routes, so I came to open them.” After al-Zubayr Pasha’s campaign in Darfur ended and security was re-established there, Abdallah al-Ta’ayshi and his family migrated toward the Holy Lands in fulfillment of their father’s dying wish that they emigrate to Mecca and never return to Sudan. During this journey, al-Ta’ayshi heard of Muhammad Ahmad al-Mahdi and sought him out until they met, succeeding in convincing him to proclaim his Mahdism.

The Mahdi elevated Abdallahi wad Turshin al-Ta’ayshi to a high position in his call and movement. On January 27, 1883, the Mahdi issued a proclamation defining the Khalifa’s status in the state, the call, and the belief. He placed him in the Islamic rank of Abu Bakr al-Siddiq and appointed him as supreme commander of all Mahdist armies, attributing all his actions to him: “The Khalifa Abdallah is part of me, and all his deeds are inspired by God and not from his whims or personal opinion.” The Mahdi’s proclamation announced the infallibility of his successor: “Know, O beloved ones, that the Khalifa Abdallah, successor to al-Siddiq, adorned with the necklaces of truth and verification, is the successor of the successors and the commander of the Mahdist armies, as indicated in the Prophetic presence! That is Abdallah ibn Muhammad—may God bless his outcome in both worlds. So wherever you learn that the Khalifa Abdallah is from me and I from him, as indicated by the Master of Existence, behave with him as you behave with me, submit to him outwardly and inwardly as you submit to me, believe his words, and do not accuse him in his actions, for all that he does is by order of the Prophet or with our permission. If you understand this, speaking against him brings calamity, abandonment, and the stripping of faith. Know that all his actions and rulings are carried on correctness, for he has been given wisdom and decisive speech.”

However, historical accounts portray Khalifa Abdallah as a man of sharp temperament, intense emotion, and a propensity for quick anger. These traits reflected in his decision-making style; he tended toward immediate resolution, clinging to his opinion and rejecting advice or counsel. He was also attributed with excessive suspicions and mistrust of others, convinced that sincerity and honesty were impossible traits. He was further known for his love of praise and flattery, inclining to listen to those who prefaced their speech by highlighting his virtues and attributing successes to his wisdom, justice, courage, and generosity—a compensatory behavior that bolstered his self-confidence and pride in his status. It is recounted that he had profound faith in his abilities, to the extent of believing he could achieve what exceeded human capacity, attributing it to a divine power supporting him.

Al-Ta’ayshi persisted with this behaviour right up to the fall of the Mahdist state to the Anglo-Egyptian invasion. The Khalifa met this invasion with an army full of courage and valor, but it was ultimately weakened by al-Ta’ayshi’s refusal to heed advice amid widespread grievance and injustice. Winston Churchill, who served as a war correspondent in Kitchener’s invading army, described the soldiers of that army in his book The River War as “the bravest who ever walked the earth,” adding that “they were not defeated but destroyed by the might of the machine.” These testimonies were echoed by other English historians, such as George Warrington Steevens. In his book With Kitchener to Khartoum, Steevens described the absurd scene of the Khalifa’s soldiers standing with unparalleled bravery, wielding rusted spears and worn rifles against the advanced British war machine, fortified by an overwhelming inner strength. He described what happened in the assault on Omdurman—the capital of the Mahdist state at the time—as “not a military battle but an execution, due to the superior firepower overwhelming a host of spears and a few rifles.”

In the final council convened by the Khalifa before the Battle of Karari, the Mahdist leaders offered their advice. Prince al-Zaki Osman, a prominent Ta’aysha commander, presented a plan that was more than a mere military tactic; it was a decisive test of Khalifa Abdallah’s leadership and the state’s vision. With Kitchener’s army advancing on Omdurman, these leaders argued that the logic of war necessitated a strategic withdrawal to their strongholds in Kordofan and Darfur. Prince al-Zaki, said: “Omdurman, my lord, is not our land to stand and defend it; it is better for us to take our men and weapons to Kordofan. If the British army follows us there—and it will not do so without much preparation and a long time—we abandon it to Shakka, which is our homeland. If it comes to us there, we fight it and defend our homeland until we triumph or die.” The Khalifa responded with a humiliating slap and expelled him from the council.

Some may interpret the Khalifa’s rejection as a commitment to the unity and sovereignty of the entire Mahdist state, refusing to partition it. Others view it as a failure to be flexible, arguing that sacrificing the capital was necessary to preserve the state’s essence and fighting capacity. But in all cases, his reaction reflects his extreme intolerance for differing opinions and the consultation for which he had convened his council.

The Khalifa waged his final war with his internal front in its worst state of fragmentation and collapse. To the point that the most famous chant of that day was that of the martyr Ibrahim al-Khalil (a young commander in the Mahdist army ranks, aged 26 at the time), addressing the Khalifa before the Battle of Karari: “Good is in what God chooses; the Mahdiyya is your Mahdiyya, and we will close any gap in our side—except for victory, there is none.”

Ibrahim al-Khalil offered not advice but his life in sacrifice for the homeland. The cry of Sudan’s dervishes—the soldiers of its national army that day—rose as they faced death: “Close the gap!” It was a desperate final cry of valor, representing a conscious choice of death in defense of the freedom of their homeland’s, not the Khalifa’s leadership or Mahdism, even if that homeland was the last inch they stood upon.

On that day, two visions clashed: the vision of military tactics and political calculations for withdrawal to survive, held by the leaders and politicians, and the vision of grand national sacrifice in defense of national liberation, held by the soldiers who chose their trenches as their graves. This scene is still witnessed by Omdurman earthen ramparts on the Nile’s banks (Ṭābiya Omdurman), which were not mere defensive lines but shrines of heroism where Sudan’s soldiers fortified themselves with legendary bravery against the savagery of the invader’s advanced artillery. This scene paralleled ancient Greek epics, but it happened here in reality and became etched in Sudanese memory: warriors with bare chests facing the deadliest products of the Industrial Revolution. The dervishes of Omdurman did not fall as casualties but ascended as symbols of the fusion of land, body, and blood. Karari was not merely a battle but an epic farewell to Africa’s first national liberation state. The battle’s outcome—and perhaps Sudan’s subsequent fate—was the tragic result of this epic.

From Revolution to State: Roots of Post-Colonial Studies in Sudan

Critics of the Khalifa note that after the Mahdi’s death, the trappings of power appeared in his appearance and conduct. Before the Mahdi’s death, he wore the patched jubba like other dervishes, but upon assuming the caliphate, he made his jubba from fine white cotton without patches, edged with colored ribbons. He wore cotton trousers and wrapped a white turban around a silk cap made in Mecca. Initially, he wore sandals like the other dervishes, then replaced them with darkish leather slippers. When he rose to walk, he carried a beautiful sword in his left hand and a small, finely crafted spear from the Hadendowa tribe in his right, using it as a staff. He walked only surrounded by a ring of young slaves who served and protected him, most of them sons of Ethiopians captured in battles. When his procession moved to a place, a long horn with a disturbing sound, made from rhinoceros horn and called the ambayo, was blown, and drums were beaten, so people knew al-Ta’ayshi was leaving his court and lined up to greet him. He imposed harsh protocols on those around him that humiliated dignity and broke spirits. Upon entering his presence, one would stand with head bowed, hands crossed on the chest, awaiting permission to sit. He himself sat reclining on a cotton pillow atop a low seat covered with sheepskins, enveloped in silent awe. Even those permitted to sit among distinguished guests sat on the ground staring at it, not moving until ordered to depart, leaving in silence.

He then proceeded to favor his kin from the Arab tribes of Darfur and exclude others. He engaged in conflicts even with the Mahdi’s family and relatives, known as the Ashraf, imprisoning some of them. This despotism led to widespread violations and massacres. The most horrific was the attack by Emir Mahmud wad Ahmad (the Khalifa’s nephew) on the Ja’aliyyin and Shaiqiya tribes in al-Matamma in early July 1897. His army of about 10,000 fighters launched a ferocious assault on al-Matamma, wreaking havoc with killing, looting, enslavement, and rape, in what was called the “Massacre of al-Matamma,” claiming around 5,000 lives out of the city’s 7,000 inhabitants at the time. The causes of this massacre began with escalating tensions between the Khalifa and the Ja’aliyyin tribes in northern Sudan, who had initially supported the Mahdist revolution but faced increasing repression from his successor. The Khalifa imposed exorbitant taxes on them, forced some into compulsory migration from their homelands to support wars, and aroused their anger with his clear favoritism toward the Baggara tribes (his own) in distributions and positions, leading to feelings of marginalization and injustice. The Khalifa then demanded that the Ja’aliyyin evacuate their capital al-Matamma to make it a defensive fortress for his army, with men leaving and women remaining, addressing their leader Abdallah wad Saad: “We want from you provisions and the fine woman.” This provoked the Ja’aliyyin and their kin.

In June 1897, the Ja’aliyyin declared their rebellion under the leadership of Abdallah wad Saad in al-Matamma. He was fiercely devoted to the Mahdiyya and played a major role in two strategic events that contributed to the Mahdist revolution’s victory over Turkish colonialism in 1885. The first was the fall of the Berber garrison, a painful blow to the morale of the capital Khartoum, besieged by the Mahdi’s army while General Gordon fortified it. The second was leading the resistance to General Wolseley’s campaign aimed at relieving Khartoum, delaying the relief expedition by five days during which Khartoum fell. This was alongside battles with British land battalions in areas like Abu Tulayh, including the Battle of Abu Rumad on the western outskirts of al-Matamma, where forces under Ali wad Hilu succeeded in killing the British commander, ending the British relief campaign and declaring the Mahdiyya’s final victory at the time. In June 1897, the Ja’aliyyin demanded an end to despotism, rejected exorbitant taxes, and refused the Khalifa’s demand to leave their settlements. The Khalifa responded by sending his nephew Emir Mahmud wad Ahmad with an army of 10,000 fighters, mostly from Baggara tribes, to suppress the rebellion. The army besieged the city for days, then stormed it in early July, committing a widespread massacre: thousands of Ja’aliyyin and Shaiqiya were killed, including women and children, with extensive looting of property, enslavement, rape, and complete destruction of the city. The massacre continued for months, leading to thousands more deaths in surrounding areas, mass displacement, and internal weakening of the Mahdist state a year before its fall.

Weaponizing History and Simplifying the Present

These are indisputable historical facts, but is it appropriate to project this historical reality onto what is happening today, leaping over all political, epistemological, and structural developments in Sudanese political practice, state structure, and analysis of the current moment as if we were in the late nineteenth century? Any analytical approach requires a precise separation of contexts to avoid biased confusion. Amid the bloody scene Sudan is experiencing today, existential questions about identity, legitimacy, and the struggle for power surface. These questions cannot be understood in isolation from Sudan’s entire modern history without treating it mechanistically. The Rapid Support Forces’ coup attempt on April 15, 2023, which ignited the war, is not a product of the Mahdist state’s battles. Rather, it is the result of eroded national sovereignty, the privatization of official violence tools, and the emergence and evolution of proxy fighting militias over the past four decades, in addition to normalizing military coups as a means of power rotation.

Here emerges the core problem in employing the history of the Mahdist revolution and the rule of Khalifa Abdallah al-Ta’ayshi to interpret the present reality: a simplistic view of history does not offer a balanced reading but reproduces an ethnic discourse exploited in the ongoing conflict. The militia and its allies use this discourse to justify their war and crimes, covering their true motives of authoritarianism and external affiliations. They also employ it as a tool to expand mobilization and recruitment on ethnic bases. In turn, some opponents resort to the same discourse ideologically to fuel enmity against the militia. However, it simultaneously deepens societal divisions and tears the social fabric through short-sighted racist rhetoric that raises the banner of “no voice above the battle’s voice.”

Thus, this approach not only deepens divisions but perpetuates analytical fallacies that distort scholarly engagement with history and complicate resolving the current crisis.

This pattern of distorted historical reading falls within the framework of the “ethnicization of history,” addressed by scholars like Benedict Anderson in his concept of “imagined communities” and how historical narratives are employed to serve identity struggles. It can also be viewed through the lens of Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger on “the invention of tradition,” where past narratives are selectively used to legitimize present realities. In the context of contemporary civil wars, this biased employment of history intersects with Paul Collier’s theses on “new wars,” where ethnic identities serve as mobilization tools rather than essential causes of conflict. This aligns with Amartya Sen’s analysis of the dangers of closed singular identities and their role in fueling fanaticism and violence, contrasted with the possibility of building peace and consensus based on multiple, intertwined identities.

A rational understanding of this phase in Sudan’s history, free from blind glorification or absolute condemnation, is not an intellectual luxury but an urgent necessity to decode the present and avoid replicating its tragedies, steering clear of exploitation that harms people without benefit.

The Mahdist revolution (1881–1885) cannot be read except in its historical context: it was the pinnacle of confrontation with Turkish-Egyptian colonialism (the former Turkiyya, as termed), which humiliated the people, undermined the economy through oppressive taxes that contributed to market backwardness, disrupted social systems, and sought to dismantle Sudan’s cultural identity. Sudan had been under Ottoman-Egyptian rule since 1821, with its resources harshly exploited, campaigns to suppress local cultures, and taxes leading to famines and local rebellions. The Imam al-Mahdi’s revolution erupted not as a mere religious revolt, as the colonizer portrayed it, but as a comprehensive national liberation revolution, uniting the Sudanese popular will across its spectra against a foreign occupier. The Mahdi drew on Islamic concepts to unify tribes and social groups, using the call to jihad not as doctrinal violence or religious mandate but as an intellectual pillar for organized political resistance against tyranny. Imam Muhammad Ahmad al-Mahdi employed the Mahdist idea, with its divine promises of victory and existential myths granting adherents meaning beyond immediate reality, as a central pillar in mobilization and assembly, reshaping reality through a sacred narrative. This constituted an advanced political practice at the time, surpassing in effectiveness and depth narrow ethnic discourses—even by present standards. It provided a comprehensive framework transcending ethnic employment, self-identities, tribal affiliations, or local loyalties, offering a comprehensive framework that, in its intellectual essence, equated all adherents regardless of ethnic or tribal backgrounds. This made it politically and organizationally superior to traditional mobilization tools at the time.

In contrast, the present features a fragmented ethnic discourse through which various forces seek to invoke history—ancient and modern—selectively, employing it in a power struggle governed by narrow agendas and external ties. While this discourse can ignite momentary mobilization, it lacks the unifying energy that distinguished the Mahdist revolution and practically reproduces division and disintegration instead of building a comprehensive umbrella project.

The Mahdist call, according to the African reality of the nineteenth century, represented the most prominent embodiment of comprehensive national will. It mobilized tribes from Darfur to Sennar and from north to south in a glorious liberation project that achieved what others failed: liberating Khartoum in January 1885 after months of siege, the fall of the Egyptian-Turkish government supported by the earth’s greatest empire at the time—the British Empire—and the killing of British General Charles George Gordon. It established an independent state at the height of the Scramble for Africa, formalized by the Berlin Conference of 1884, held a year before Khartoum’s liberation. This victory was Africa’s first major triumph against European colonialism in that era, inspiring subsequent liberation movements in Africa, such as the Zulu revolt in South Africa or Emperor Menelik’s resistance in Ethiopia.

These are facts of national pride and enduring glory that cannot and must not be reduced or distorted by fabricating a causal link between them and what occurred later under Khalifa Abdallah al-Ta’ayshi’s rule. Attempts to criminalize the entire Mahdist revolution or label it as terrorism or backwardness based on the subsequent state’s practices are a form of hypothetical fallacy that judges the beginnings of struggle by its ends. It resembles judging the 1924 revolution against the British by the national state’s flaws, or the October 1964, April 1985, or December 2018 revolutions by the failure to complete democratic building—all glorious moments in Sudan’s history whose hopes and aspirations were not realized due to shortcomings in what followed.

Separating Revolution from State:Toward a Balanced Reading of the Past

The Mahdist revolution was a momentous liberation, a standalone achievement that must remain preserved in collective memory as an element of national pride and the formation of the independent Sudanese state threatened by today’s war. The revolution contributed to shaping modern Sudanese identity, becoming a symbol of unity against the external, still used in national discourses today without separating it from subsequent lessons. The Khalifa’s rule represented a coup against the project and the establishment of a security state. This state was an illegitimate betrayal of the revolution’s conditions that preceded it, but it was not inevitable. Even here, it must be judged in its historical context, not by projecting present conditions onto it. The distinction between the liberation revolution and the post-liberation state is foundational to all post-colonial studies, which clearly differentiate between revolution and the state’s reflection. After the Mahdi’s martyrdom in 1885 from the plague epidemic that spread following the revolution, the conflict with his successor was not about his person to invoke his ethnicity in judging today’s events, but about the governance approach he adopt, which constituted a coup against the revolution itself. The Khalifa’s precedence in jihad under the Mahdi’s banner and for the revolution’s noble goals cannot become a blank check justifying his subsequent deviation from those principles or covering the flaws that marred his rule’s experience.

Just as the revolution was built on the idea of justice and liberation from oppression, drawing on Islamic principles of equality and social justice, the Khalifa’s system gradually transformed into a police security state. Under the weight of external and internal threats and the absence of wise governance, it was based on narrow tribal favoritism, brutally suppressing any opposition, even from Mahdiyya symbols themselves, such as the Mahdi’s other named successors, Ali wad Hilu and Muhammad al-Sharif, who were repressed or had some followers executed.

As a ruler, Khalifa Abdallah committed grave errors in governance that could have been avoided by adhering to the spirit and values of the nascent Mahdist revolution. Yet he resorted to the same elements of corrupt rule that led to the revolution’s outbreak: internal military brutality leading to massacres in the south and west, neglect of agriculture causing the famine of year six (1889–1890 CE, corresponding to 1306 AH) that killed hundreds of thousands, the spread of diseases like cholera, imposition of exorbitant taxes, and international isolation that made the country easy prey for the Anglo-Egyptian invasion in 1898 at the Battle of Karari, where tens of thousands of Sudanese were killed. He also imposed harsh economic policies, such as land confiscation and heavy taxes to finance wars, weakening the state internally and sparking tribal rebellions against him.

These errors are purely political, administrative, and erroneous practices, not an inevitable continuation of the revolution’s idea. More accurately, they are a betrayal of its spirit, transforming the state from a liberation project to a despotic system relying on repression for survival. Here again, the Khalifa must be judged historically by his era’s standards: What was the context in which he operated, with colonial empires threatening all? What were the internal challenges after a revolution leading to economic chaos? What alternatives were available in the nineteenth-century world where dictatorships were common in Africa and Asia? How did his contemporaries rule in Africa and the world, such as Emperor Tewodros in Ethiopia or Sultan Abdul Hamid in the Ottoman Empire? This is an objective judgment entirely different from absolute contemporary condemnation that projects twenty-first-century concepts onto nineteenth-century reality, or that confuses the act of liberation with the act of governance, thereby distorting the revolutionary legacy. Likewise, this objectivity does not justify absolute crimes like his violence toward his people or repeating the policies that sparked the revolution which created his state in the first place.

Here we delve into the core of the intellectual crisis fueling Sudan’s political crisis today. There is a prevalent discourse either wholly whitewashing history or wholly criminalizing it, both forms of biased epistemological trap. This trap leads the nation to repeat its tragedies instead of learning from them. In Sudan’s modern history, we see this repetition clearly: after independence in 1956, the country witnessed repeated coups, such as Abboud’s in 1958, which formed the first breach of democratic state-building principles; then Jaafar Nimeiry in 1969, which began as a socialist revolution but turned into a repressive Islamist dictatorship; and likewise under Omar al-Bashir (1989–2019), who came via an Islamist Brotherhood coup then proceeded to establish a corrupt and despotic rule, extinguishing civil war flames in southern Sudan only to ignite others in Darfur. Similarly, the Empowerment Dismantling Committee after the December 2018 revolution followed the same pattern of failing to learn from mistakes by attempting to replace one political faction’s empowerment with another’s.

Reconciling with the Nation’s Memory

While some compare the Janjaweed’s brutality today to al-Ta’ayshi’s rule, these critics overlook several methodological points that invalidate this comparison:

- Invoking history as an ideological weapon, not a reference for learning: Figures like Khalifa al-Ta’ayshi are studied not to understand governance contexts and errors but to discredit the current political adversary. It is the same exclusionary security logic that turns politics into existential war.

- Confusing revolutionary legitimacy with governance legitimacy: Many factions today imagine that their legitimacy derived from past struggle (or its claim) grants them the right to monopolize power and eternally exclude others, forgetting that governance legitimacy stems from wise administration, justice, services, and meeting people’s needs, not merely affiliation with a specific revolutionary history. This is the same predicament of the Khalifa, who believed the Mahdi’s revolutionary legitimacy inherited automatically, neglecting to build new governance legitimacy based on popular consent and achievement.

- Normalizing ethnic politics and narrow tribal and regional alliances: Just as the Khalifa relied on narrow tribal alliances, today in Sudan we see alliances based on primary loyalties (tribal, regional, sectarian) more than on a comprehensive national political project or orientation. This entrenches division and makes the power struggle existential rather than political and resolvable.

- Entrenching a culture of exclusion and brutality: The model the Khalifa established in dealing with opposition—repression and brutality—still inhabits the Sudanese political mind. Instead of viewing difference as a natural part of the political process, it is treated as a tool for stigmatization and exclusion, pushing disagreement from the realm of political competition to military conflict with no victor or vanquished, only total destruction.

To break this vicious cycle, a radical separation process is needed among the three components deliberately or ignorantly confused:

- Separating the liberation revolution with all its high symbolism from the experience of governance and administration: Pride in the act of national and social liberation does not mean exonerating all that followed. We can take pride in the Mahdiyya as Africa’s greatest liberation movement in the nineteenth century without overlooking the errors of the Khalifa’s state. This separation frees historical symbols from being hostages to present exploitations and allows the Mahdist legacy to build true national unity, as in the peaceful 2018–2019 revolution that toppled al-Bashir but failed to evolve toward state stability due to contention over the state as spoils.

- Separating historical critique from contemporary criminalization: Judging Khalifa al-Ta’ayshi historically according to his era’s conditions and reality—meaning analyzing his context, choices, errors, and responsibilities—is the task of objective historical engagement. Insulting his experience or portraying him as an absolute devil serves nothing but drowning the present in irresolvable conflicts after two centuries. Historical critique aims at understanding and heeding, not insult or exclusion.

- Separating identity from power: The greatest error successive Sudanese elites committed is linking Sudan’s identity to the ruler’s or system’s identity. The failure of the Khalifa’s state does not mean the failure of Sudan’s idea, just as the failure of al-Bashir’s or others’ regimes does not. National identity is broader and deeper than any governance system and is the framework that must encompass all. In the war’s context, this means rejecting parallel governments and calling for reconciliation including everyone.

Sudan’s war today is a war over power and resources, in which internal and external parties vie to deprive the Sudanese people of their inherent and natural rights to their land. But it feeds on distorted historical consciousness, full of old wounds that have not healed and conflicting narratives that have not reconciled. Emerging from it requires, alongside a ceasefire and political negotiations, reconciliation with history first—a reconciliation that acknowledges the revolution’s glories and the state’s failure together, distinguishing between the sanctity of struggle and imprudent governance. It understands that critiquing the past is not detachment from it but an attempt to draw lessons for building a tomorrow where we do not repeat yesterday’s mistakes. Only by unraveling this toxic entanglement between past and present can Sudan begin to decode and heal its wounds instead of continuing the confusion that will lead to further destruction.