Conflict, Famine, Agricultural Resilience and the Future of Humanitarian Strategy in Sudan

Conflict, Famine, Agricultural Resilience and the Future of Humanitarian Strategy in Sudan

Amgad Fareid Eltayeb

Since the outbreak of war between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the Rapid Support Forces in April 2023, Sudan’s agricultural and livestock sectors—long central to the national economy—have faced severe disruption. The incursion into Al-Jazira State in particular led to a complete halt in farming activities and damaged key infrastructure in the state, participating to a major food crisis and pushing several in Sudan toward famine.

In stark contrast to prevailing challenges, a March 2025 Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) report illuminates remarkable resilience and recuperation within Sudan’s agricultural sectors. The findings stem from the FAO’s Crop and Food Supply Assessment Mission (December 2024 – January 2025) in nine secure states under Sudanese Armed Forces control, namely Al-Jazira, Gedaref, Blue Nile, Kassala, Red Sea, Northern, River Nile, Sennar, and White Nile, supplemented by remote data collection for conflict-ridden areas (Khartoum, Darfur, Kordofan) to comprehensively assess the 2024/2025 agricultural output. A multifaceted methodology involved structured interviews with governmental, UN, and NGO entities, direct consultations with agricultural stakeholders, and the leveraging of satellite imagery and vegetation data to empirically ground field observations. This juxtaposition of systemic fragility and resilient recovery underscores the profound adaptability of Sudan’s agrarian communities.

Grains Against the Storm: Sudan’s Agricultural Reckoning

The report’s most compelling findings highlight a significant achievement in agricultural production for the 2024 seasons, which has marvelously overcome the setbacks of the war’s onset in 2023, though full recovery remains on the horizon. Total cereal production soared to 6.7 million metric tons, reflecting an impressive 62% increase over the previous year and a 7% rise above the past five-year average of 6.26 million metric tons. This harvest included:

- Sorghum production: Achieved a 5.4 million metric tons, which is a 77% surge from 2023 (3.06 million metric tons) and a 30% increase over the five-year average (4.15 million metric tons), underscoring the sector’s dynamic recovery.

- Millet production: Reached 792,943 metric tons, marking a 16% improvement over 2023 (683,000 metric tons), though it remains 45% below the five-year average (1.44 million metric tons).

- Wheat production: Attained 490,320 metric tons, a notable 30% rise above the prior year’s average (377,000 metric tons), yet 22% below the five-year average (629,000 metric tons).

Furthermore, the total cultivated area for cereal crops expanded to 15.1 million hectares, reflecting a commendable 10% increase over the 2023/2024 season (13.7 million hectares) and a 5% rise above the five-year average (14.4 million hectares). This expansion reflects the indomitable spirit and adaptive ingenuity of Sudan’s agrarian communities to enhance productivity and reclaim arable land amidst ongoing challenges, further bolstering the optimistic trajectory of recovery delineated in the FAO’s March 2025 report. Remarkably, this expansion occurred even as large swaths of arable land in Khartoum, Darfur, and Kordofan remained under the RSF militia control during 2024, that prevented considerable farming activities taking place. It further underscores the latent potential for expanding Sudan’s agricultural production, illustrating the sector’s underlying resilience and capacity for growth even amid conflict and instability.

This achievement was partially enhanced by an exceptional rainy season. Data from the Vegetation Health Index indicated excellent vegetation conditions in October 2024, following a well-distributed rainfall pattern that began in July of the same year. However, this success was realized despite a severe shortage—and rising cost—of agricultural inputs, including seeds, fertilizers, pesticides, machinery, fuel, and labor. These challenges were compounded by the ongoing war, which drove inflation above 240% by late 2024 and caused a sharp depreciation of the Sudanese pound, falling to SDG 2,445 per U.S. dollar in December 2024, compared to SDG 1,100 per dollar in December 2023 and SDG 603 per dollar in March 2023, prior to the outbreak of the conflict.

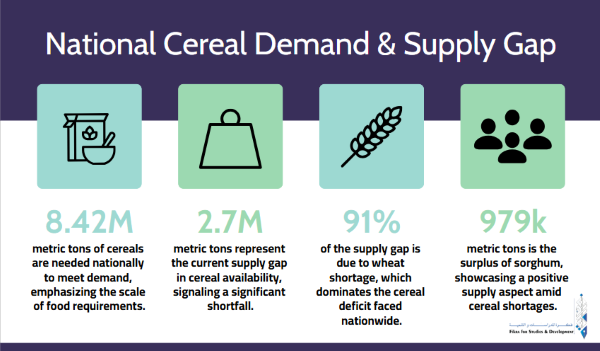

This promising level of production is expected to significantly contribute to meeting the country’s food needs. With an estimated population of 50.7 million in 2025, the annual demand for cereals stands at approximately 7.715 million metric tons, based on an average per capita consumption of 152 kilograms—comprising 75 kg of sorghum, 58 kg of wheat, 16 kg of millet, 2 kg of rice, and 1 kg of maize. In addition to human consumption, a portion of these cereals is allocated for animal feed—estimated at 285,540 tons (5% of sorghum and 2% of millet)—as well as for use as seed grain, amounting to 116,960 tons. Post-harvest losses are projected to reach 314,230 tons. Altogether, Sudan’s total cereal requirements are estimated at approximately 8.42 million metric tons.

With domestic cereal production estimated at 6.7 million metric tons and pre-existing stocks totaling 9,151 tons (comprising 1,540 tons held privately, 3,262 tons by humanitarian organizations, and 4,349 tons in the government strategic reserves), a supply gap of approximately 2.7 million tons remains—one that must be bridged through imports.

Wheat constitutes the overwhelming majority of this gap, accounting for 91% of the shortfall. Nevertheless, a surplus of sorghum—estimated at around 979,330 tons—is expected, which could bolster national reserves and potentially help reduce import needs if strategic exchange agreements are negotiated with international agencies, particularly the World Food Programme. It is also important to note that the reliance on wheat as a dietary staple is a relatively recent phenomenon in Sudanese food culture. Traditionally, rural and agrarian communities have relied predominantly on sorghum and millet as their primary staples.

This year’s production has already contributed to a reduction in the market prices of domestically produced sorghum and millet by 20% and 10%, respectively, between October and December 2024, coinciding with the start of the marketing season for the 2024 harvest. However, despite these declines, prices remain nearly five times higher than their pre-conflict levels in April 2023.

The Endurance of Sudan’s Livestock Sector

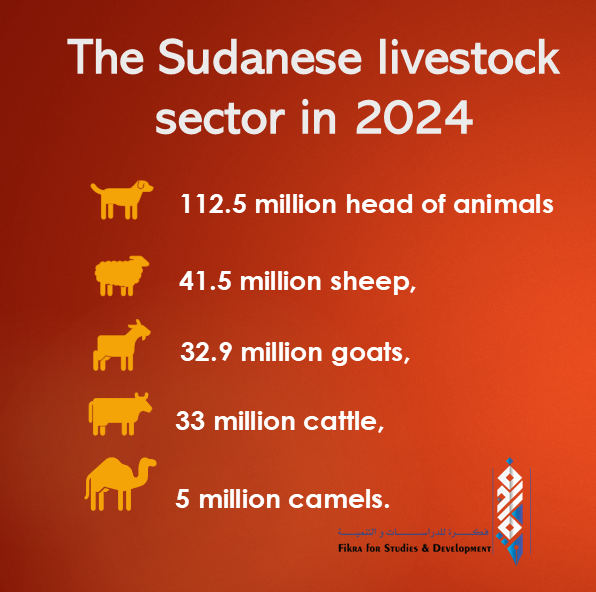

The Sudanese livestock sector, comprising an estimated 112.5 million head of animals—41.5 million sheep, 32.9 million goats, 33 million cattle, and 5 million camels—has also demonstrated remarkable resilience in the face of ongoing turmoil. In 2024, livestock conditions showed a notable improvement compared to 2023, primarily due to abundant rainfall that significantly enhanced pasture quality, ranging from good to excellent, with favorable grazing conditions expected to continue through March 2025.

Government efforts have succeeded in vaccinating approximately 8.2 million animals in relatively secure areas under the control of the Sudanese Armed Forces, despite the domestic suspension of vaccine production caused by the conflict. International support, particularly from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and other agencies, provided imported vaccines to help fill this gap. However, security constraints have led to the concentration of herds in states such as Gedaref and Kassala—raising concerns about early pasture depletion and overgrazing.

The war-induced deterioration of the broader economic situation has led to a sharp rise in livestock prices. For instance, the price of a single dairy cow surged to 3.5 million Sudanese pounds (approximately USD 1,432 at the May 2025 exchange rate of SDG 2,445 per USD), marking a staggering 438% increase from December 2023, when the price was SDG 800,000 (around USD 327).

Livestock exports rose to 5 million head in 2024, a 10% increase compared to the previous year. Nevertheless, this remains significantly below pre-war export levels, which reached approximately 7 million head annually in 2018. These figures also exclude losses incurred from the complete halt in the export of slaughtered and frozen meat. Moreover, the resurgence of localized diseases—such as lumpy skin disease and foot-and-mouth disease—poses a serious threat to these gains, particularly given the weakened state of routine vaccination campaigns that had previously been regularly implemented before the war.

Beyond Relief: Rethinking Humanitarian Strategy in Sudan

Despite modest gains in agricultural and livestock production, the ongoing conflict remains the most significant threat to food security in Sudan. The war has displaced 11.6 million people—8.84 million internally since April 2023, in addition to 2.73 million already displaced before the conflict—and forced another 3.5 million to flee across borders, primarily to Chad, South Sudan, and Egypt.

Currently, an estimated 24.6 million people—half of Sudan’s population—are experiencing acute food insecurity. This includes 8.1 million individuals in the emergency phase and 637,000 in the catastrophic phase, with famine risks looming in multiple regions, including North Darfur, West Kordofan, South Kordofan, Al-Jazirah, and Khartoum.

Structural Strains and the Urgency of a New Humanitarian Paradigm

The disruption of commercial routes due to ongoing insecurity has driven fuel prices up by an estimated 150% to 250%. This surge in fuel costs has, in turn, inflated the expenses associated with both agricultural production and transportation, exerting additional upward pressure on food prices. Although the prices of sorghum and millet declined by 20% and 10% respectively between October and December 2024, they remain five times higher than their pre-war levels.

Further compounding the crisis is the acute shortage of certified and high-quality seeds—only 5,297 metric tons were distributed by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) ahead of the last planting season. Additionally, the degradation of irrigation infrastructure, particularly in major agricultural schemes such as the Gezira Project, has severely undermined productivity. The deliberate destruction of this vital scheme by the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) during their occupation of Gezira State exemplifies the strategic targeting of national food systems. These challenges are exacerbated by a broader economic collapse, with GDP contracting by 29.6% in 2024 and inflation soaring to 240%—both of which intensify the fragility of Sudan’s food security landscape.

The experience of Sudan during the ongoing war, which erupted in April 2023, underscores the urgent need to reassess the prevailing paradigms of humanitarian response—particularly with regard to food security. International aid systems have largely prioritized the importation of externally sourced food assistance. Yet, Sudan’s agricultural sector—despite the ravages of war, institutional collapse, and severe resource scarcity—has demonstrated a remarkable capacity for resilience and recovery.

Regaining Food Sovereignty in a War-Torn Nation

This extraordinary performance, as documented in the UN’s Crop and Food Supply Assessment Mission (CFSAM) report, affirms that reliance on local food production is not a theoretical ideal but a practical, proven, and effective pathway. It calls for a fundamental shift in how the international community supports crisis-affected countries—prioritizing the reinforcement of endogenous food systems over dependency on imported aid.

This evolving dynamic necessitates a strategic shift in the operational approach of international and regional humanitarian organizations—away from emergency-based import models toward a more sustainable and effective paradigm. Central to this transformation is the localization of aid efforts through the strengthening of local agricultural capacities. This includes the timely provision of essential inputs such as seeds, fertilizers, machinery, and fuel, along with targeted support for small and medium-sized food industries, which form a critical link in the food value chain.

Such a paradigm shift does not merely enable the localization of humanitarian assistance—it also substantially reduces costs. In a context marked by declining global humanitarian funding and shrinking resources allocated to Sudan, localization emerges not as an aspirational slogan, but as a demonstrably more efficient and cost-effective alternative. By reinforcing local food production chains, this approach increases resilience to shocks, reduces dependency on external aid, and generates significant multiplier effects across the economy.

This is particularly critical in Sudan, where agriculture remains the primary economic activity for over 65% of the population and accounted for nearly 25% of GDP in the pre-war years (2020–2022). Investing in this sector is not only a means of addressing immediate food needs—it is an investment in social stability, community resilience, and the structural recovery of Sudan’s macroeconomic foundation.

Therefore, any realistic strategy to confront Sudan’s food crisis must be grounded in the local context. Supporting domestic agricultural and food production should be regarded not merely as a food security intervention, but as the cornerstone of broader economic and social recovery—both in the near term and over the long arc of national reconstruction.

Conclusion of Main Recommendations

In light of Sudan’s escalating food security crisis, there is a critical need for a paradigm shift among all stakeholders—national actors, international donors, and humanitarian agencies—toward strategies rooted in evidence-based, locally anchored resilience. Externally driven food aid models, while necessary in acute emergencies, often undermine long-term agricultural self-sufficiency and economic sovereignty. The following recommendations draw on both Sudan’s internal capacities and global best practices, advocating for a scientifically grounded, system-oriented approach that prioritizes endogenous food systems, localized production, and structural recovery as the foundation for sustainable peace and development.

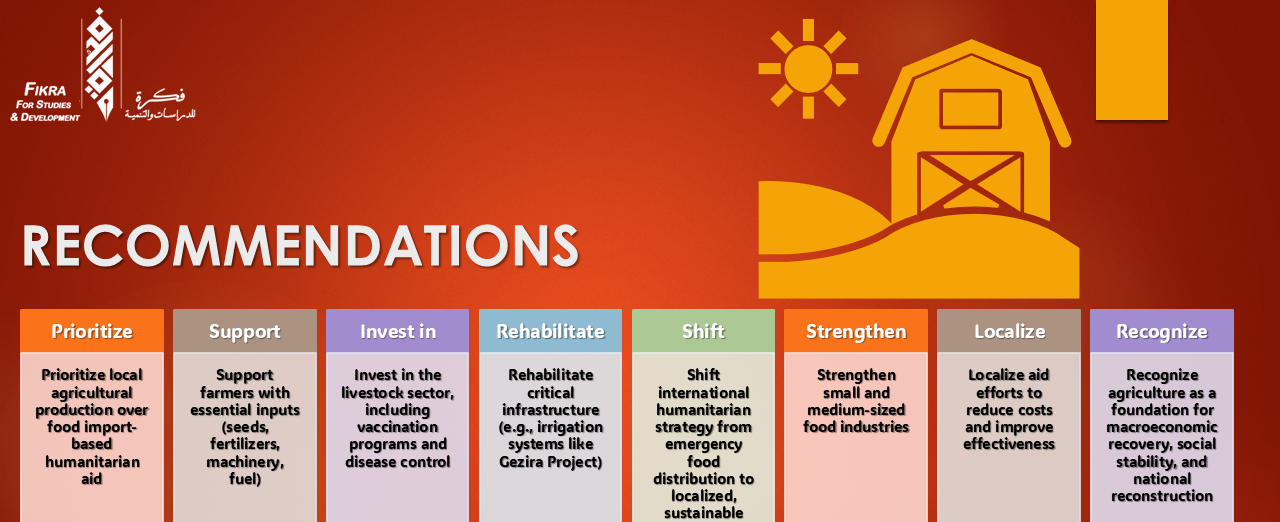

- Prioritize local agricultural production over food import-based humanitarian aid to enhance food security and resilience.

- Support farmers with essential inputs (seeds, fertilizers, machinery, fuel) to sustain and expand domestic food production.

- Invest in the livestock sector, including vaccination programs and disease control, especially in secure areas.

- Rehabilitate critical infrastructure, such as irrigation systems (e.g., Gezira Project), to restore productivity.

- Shift international humanitarian strategy from emergency food distribution to localized, sustainable support models.

- Strengthen small and medium-sized food industries as vital links in the food value chain and rural economies.

- Localize aid efforts to reduce costs, improve effectiveness, and build long-term self-reliance.

- Recognize agriculture as a foundation for macroeconomic recovery, social stability, and national reconstruction.